Are you concerned about cruelty to animals and the, often, light punishments that are served to offenders? This report sheds light on the situation in Victoria, Australia….

New report shines light on who commits animal cruelty and how they are punished

The Sentencing Advisory Council has just released the first ever review of how animal cruelty offenders are sentenced in Victoria.

That report was developed in response to growing community concern about how animal cruelty offenders are sentenced. Several cases have received significant media attention. The report was also designed to provide an evidence base for the government when it overhauls Victoria’s animal cruelty legislation this year, which it described in 2018 as “outdated”.

Read more:

Australia increasingly uncomfortable with animal cruelty

What is animal cruelty?

One of the most noteworthy findings in the report is that most animal cruelty offending sentenced in Victoria does not involve deliberate or malicious forms of cruelty (such as beating or torturing a pet).

Instead, the majority of animal cruelty resulting in sentences in Victoria is the result of neglect-related behaviours, such as failing to provide sufficient food, drink, water, shelter or veterinary treatment to an animal. That type of offending made up at least half, but probably closer to three-quarters, of all animal cruelty offences between 2008 and 2017.

This is consistent with observations in RSPCA Victoria’s annual report, which noted that “the majority of reports that we receive seem to be the result of ignorance or inability rather than malice”.

Who committed these offences?

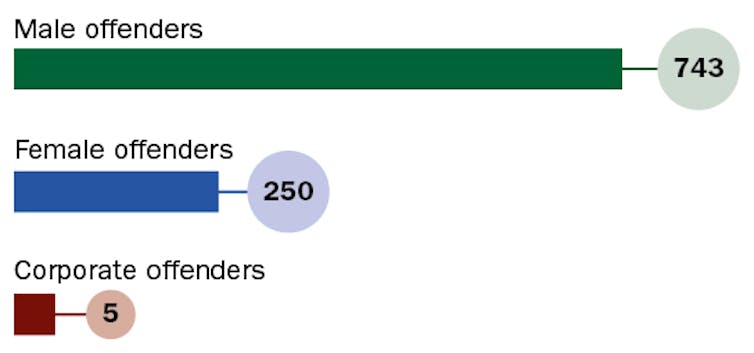

From 2008 to 2017, at least 998 offenders were sentenced for animal cruelty in Victoria. That’s about 100 per year. Men represented almost three-quarters of those offenders, and a quarter were women. Less than 1% were corporations.

To put this in context, this is slightly less than the rate at which men are sentenced for all offending in Victoria. In the most recent financial year, Victorian courts sentenced over 100,000 cases. Four out of five offenders in those cases were male (79%).

However, there was a subgroup of animal cruelty offenders – those whose case was flagged as involving family violence – who were much more likely to be male. Of the 231 animal cruelty cases sentenced in 2016 and 2017, 15% of cases were flagged as related to family violence (35 cases). And of those 35 offenders, 33 were male.

Who prosecutes animal cruelty?

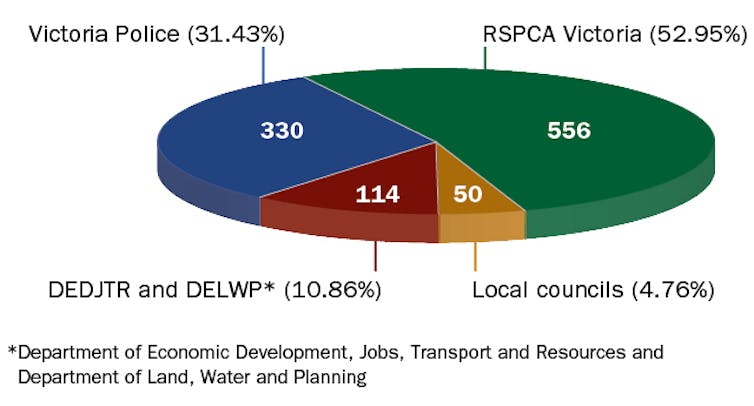

Two agencies, Victoria Police and the Office of Public Prosecutions, prosecute most crimes in Victoria. However, the responsibility for prosecuting animal cruelty offences also falls on local councils, two additional government departments and RSPCA Victoria.

In fact, RSPCA Victoria is one of the only non-government bodies in the country with the power to prosecute people for criminal offences. It was responsible for prosecuting more than half of all animal cruelty cases in Victoria in the past ten years.

Victoria Police prosecuted the second-largest number of cases. Police usually discover animal cruelty when a neighbour has reported what they think is animal cruelty, or when officers enter a house for some other reason, such as executing a search warrant or responding to a report of family violence.

How many animal cruelty offences were there?

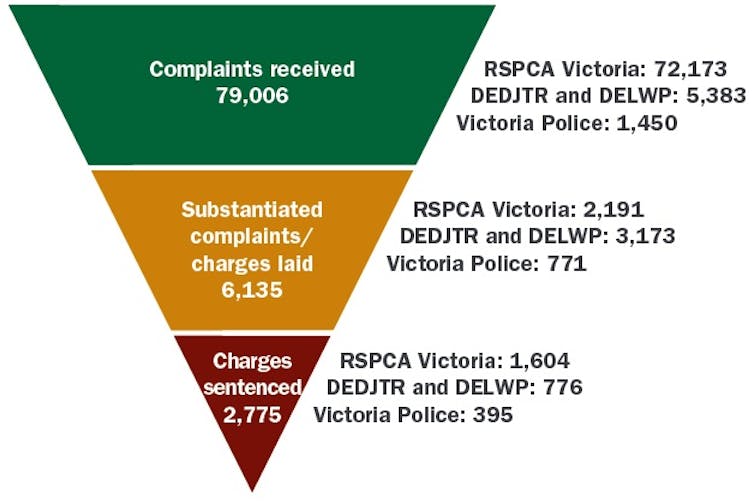

Nearly 3,000 charges of animal cruelty were sentenced in Victoria from 2008 to 2017. But this does not represent all animal cruelty that occurred in the state during those ten years. A lot of animal cruelty is never discovered or investigated, in large part because the victims are unable to speak for themselves.

There are also many complaints about animal cruelty that don’t result in a sentence being imposed. For example, between 2011 and 2017, 79,000 complaints of animal cruelty were to the various prosecuting agencies. Those complaints led to just over 6,000 charges being laid, which in turn led to nearly 2,800 offences being sentenced.

There are good reasons for this disparity between the number of complaints and charges sentenced. For one thing, many complaints of animal cruelty don’t actually constitute cruelty, such as a neighbour complaining about a dog being left in the backyard for the day.

More importantly, though, the legislation these agencies are enforcing is “directed at animal welfare rather than enforcement of the criminal law”. In other words, a criminal justice response is a last resort and in many cases will not be the most appropriate way of ensuring animal welfare.

How were animal cruelty offences sentenced?

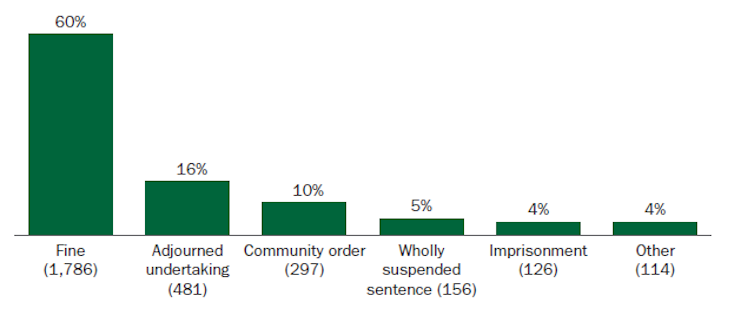

Of the 3,000 charges that were sentenced, 60% resulted in a fine and 4% in a term of imprisonment. The average fine was about $1,400 and the average prison term was three months.

The high rate of fines for animal cruelty warrants further consideration. Not only has the Sentencing Council’s previous research found that 40% of fines in Victoria are never paid, but more importantly, if the offender is a farmer who is struggling financially and has been unable to water, feed or medicate their livestock, it would seem incongruous to burden them further with a monetary penalty. Alternatively, if the offender engaged in more deliberate acts of cruelty, this would usually indicate that some form of rehabilitation is needed.

When sentencing an animal cruelty offender, courts in Victoria have an option available to them known as a “control order”. This is an order that either prohibits or restricts the offender’s ability to own or be in charge of animals. It can also place conditions on their ability to have animals. For example, one farmer was ordered to undertake a sheep management course and pay for a vet to regularly inspect any livestock under his care.

The council found that a control order was imposed in just 20% of animal cruelty cases. The rate was particularly low in cases prosecuted by Victoria Police (less than 1%). Yet when the council spoke to prosecutors responsible for animal cruelty cases, they said that often the most desirable outcome of the criminal proceedings is to have a control order imposed.

There is a question, though, about whether agencies would have enough resources to monitor control orders if they were imposed more often. That would involve a lot of extra work, which would, in turn, require additional resources.

Where to from here?

The findings in this report are consistent with similar research in Queensland, New South Wales and most recently South Australia. Men are the most common offenders of animal cruelty, and fines are the most common sentence imposed.

Read more:

Penalties for animal cruelty double in SA, but is this enough to stop animal abuse?

It is hoped this report will prompt discussion about the role of the criminal justice system in responding to animal cruelty. Given the high rate of neglect-related offending – which is usually because the person either didn’t know how to care for their animals or didn’t have the resources to do so – is the criminal law the best response to those sorts of behaviours? And if it is, what should that response look like?

We also need to consider if monetary penalties are the best way to protect animals from similar offending in the future, or if it would be better to place more emphasis on control orders and provide agencies with the resources they need to monitor them.![]()

About the authors

Paul McGorrery, PhD Candidate in Criminal Law, Deakin University and Arie Freiberg, Emeritus Professor of Law, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read more

Do fish have feelings? Animal sentience explained

What is Animal Law